A MOMENT OF ETERNITY

アートを通して未来へ種を蒔く

Words by Kenji Jinnouchi, Photographs by Hiroshi Mizusaki,Edit by Masafumi Tada

“Visit Dazaifu for an exploration into modern art.”

It’s been a while since art lovers around us started comparing notes saying something like that.

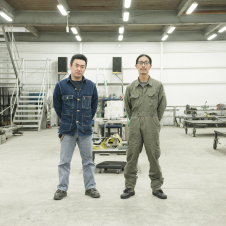

There is one key person who gave Dazaifu its reputation. His name is Nobuhiro Nishitakatsuji. He is Gonguji(deputy representative)of Dazaifu Tenmangu, and has a passionate-detailed knowledge of art.

He started “The Art Program” at Dazaifu Tenmangu in 2006 and since then, he has invited several artists leading modern art inside and outside of Japan to Dazaifu and had them mirror a new phase of Dazaifu by their creations. These great works of art are now community assets for future generations.

In January, 2014, Kambe moved to Dazaifu, and now, he is working on the creation of 24 fusuma paintings at Dazaifu Tenmangu.

For this FEATURE, we interviewed two of them about Art, Shinto and future of Dazaifu, along with Narimasa Nakaoka, who loves Kambe’s art and requested him to design wrapping paper for his Wagashi(Japanese confectionary) company, Suzukake.

C: First of all, could you tell us the story about how you met each other?

Nishitakatsuji: The first time that I met him was in October, 2008. At the time, I was in Boston for my research and we met at a party which was held at the Japanese Consulate there. There were a lot of young artists and researchers, and Kambe was invited as one of them. As a matter of fact, I knew of him before that, since there was a mutual friend between us. I was so excited to see him in person in Boston.

Kambe: I was provided with an opportunity to go to any country I wished, to work on my art research for a year as a trainee under the overseas study program for upcoming artists of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. I decided on Boston since I was hoping to visit the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and take some time to explore the art there. I knew the museum had a great collection of Oriental Art including some of Taikan Yokoyama’s work, since the first head of the Asian art division was Tenshin Okakura. First of all, I was going to work on my paintings there as well, but I realized that it wasn’t the best work environment for me, because central heating was provided inside buildings and the dry air wasn’t good for Japanese paints and materials. It would have made Nikawa dry up or bent the canvas wood. So, I changed my mind and decided to concentrate on learning about art and exploring there to broaden my horizons. Actually, I had so many opportunities to meet a lot of people who were very active in each of their fields, to visit exhibitions, events and art museums there. I had great experiences and that one year went by so fast.

Tomoyuki Kambe

Tomoyuki Kambe

C: How were cultural exchanges between the two of you in Boston?

K: Where Nobuhiro lived was near my place. It was one train station away. We would see each other almost every week. He showed me inside of his university campus, Harvard, and some of the museums in the area. We would go out of town together to visit some art events or Yale University’s museum. He helped me often with my English, too.

N: We would visit the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. to look at the works of Soutatsu Tawaraya and Korin Ogata, and drove to the west coast to look at one of Kambe’s works exhibited in the Clark Center for Japanese Art and Culture.

K: The most impressive thing we shared was how differently we looked at the same type of artwork. I was looking at them from the point of view of a creator as a Japanese-style painter. On the other hand, Nobuhiro has an eye for Art as a researcher and is also collecting art pieces. What we shared was so different all the time. We found it very interesting to learn many things from each other.

N: In Japan, it seems a little difficult to mingle with other categories of art or research including my field, but, in the US, we were naturally in a network which consisted of people from various fields of Politics, Cultures and Art to have discussions in various ways of thinking. Kambe and I would join those discussions at some workshops and have opportunities to look at the ways of other artists, or sometimes I would give some lectures about Shinto to people there. It was a very fruitful time.

Nobuhiro Nishitakatsuji

Nobuhiro Nishitakatsuji

C: Thanks to your friendships in Boston, you two have been in contact even after returning to Japan respectively, however, could you tell us the story of how you two were reunited for the 7th art program in Dazaifu?

K: Before the invitation to the program, I was invited to Dazaifu Tenmangu for their Shinkoshiki-Taisai (autumn festival), which is very important for this shrine. I had visited many shrines which are located in the Kanto area, where I used to live, and my home prefecture, Gifu. However, I noticed a different atmosphere here as soon as I entered Dazaifu Tenmangu as may be expected of the authority of one of the main shrines in Japan. Also, not only people working at the shrine, but also other people in the community supported the festival appreciating its culture and their lives there. I vaguely thought I wished to live somewhere like here someday at the time.

Nakaoka: I also saw Shinkoshiki-Taisai three years ago. I realized the difference in the flow of time here even though I live in Fukuoka city, which is located close to Dazaifu city. I think I have the strong character of Hakata as one of the folks there since I’ve been participating in Hakata Yamakasa, and my impression was: Dazaifu seems very elegant. How the people talk here is different in comparison to Hakata, which has been recognized as a mercantile city.

N: I think that is because there is a lot of influence from Kyoto culture. For example, when we talk about certain things, we add “o” before the names of the items.

Some examples are: To carry Mikoshi (portable shrine), we say “O”kata, and for the direction towards south, “O”minami.

By the way, on the occasion of inviting Kambe for the art program, he visited here many times for the research before his creation of work.

K: I came here for the research about 10 times at different seasons. During the period, the earth quake in Tohoku occurred on March 11, 2011. On that day, I was sketching in the shrine, so I didn’t know about it and one of the priests asked me, “Is everything fine with your house in Tokyo?” then I realized what had happened and how terrible it had been. I think Japan has totally changed; our society and life have changed since that day. From this experience, I decided on “A Moment Of Eternity” for the title of my work at the art program, because I strongly thought, “The fact I have been safe and sound, and am able to do my work for Tenjin(shrine spirit) like this now means I have been appointed to portray every event in a fleeting moment in life happening right in front of me, which also seems like an eternity. I wanted to express this feeling in my work.”

N: Things change sometimes, however, speaking of Dazaifu Tenmangu, it has 1100 years of history and it didn’t just happen, every single second was accumulated in the same style. We can say the same kind of thing for the time length of “Eternity”. Things sometimes change, but, on a longer time scale, things don’t change. I think “A Moment of Eternity” expresses these essences well with the beauty of nature.

K: I had drawn some other pictures of the beauty of nature, however, it was not only because I simply liked nature. I figured out why I had chosen the theme through talks with Nobuyoshi and my stay in Dazaifu: This is from the feeling of awe by the majesty of nature. A lot of Japanese share this feeling from Shinto, even though it is sometimes considered that we have no certain god with our religion by people from other countries. I learned so many things when I studied abroad and met people from various countries and one of these is: there is a huge variation in the ways of thinking in the world.

Christian, Islam, Jewish…they are all monotheistic religions, whereas we believe there are so many good spirits in everything around us and those spirits protect us. I was more convinced than ever that I would like to express this feeling from Shinto in my art, and show the value of it in today’s society no matter how much technology has changed things.

C: Are there some other things that your work and Shinto share?

K: I think both Japanese-style paintings and Shinto are now finding new ways of expression to make impacts on people, especially young people. Speaking of my work, there are some changes in painting materials. These days, it’s getting difficult to find thick Washi(Japanese paper) and the same types of pigments that we have been using in Japan because of lack of the materials for these. However, I don’t think there are only negative aspects, but there is also a positive side. For example, I make some layers with gold foil, silver foil and very thin Washi for my artwork. Very thin Washi was hard to make a long time ago, however, thanks to Japan’s high technology, it can now be made much thinner than facial tissue paper, and is capable of being 1 meter wide in a big roll. It is used for fixing ancient documents. It’s definitely one of Japan’s proudly great technologies. As one door closes, another one opens. I think Shinto has the same kind of situation as mine, taking over the original manners but creating something with new ideas.

C: Kambe has worked on the project for wrapping papers of your company, Suzukake. When did you start being attracted by his art, Nakaoka?

Nakaoka: It was in 2011, when I was looking for some artwork for my home. Nobuhiro lent me one of Kambe’s art pieces. I meant to return it after, but once I set it at my place, I started thinking I wanted to own it. Then, I asked him to let me purchase it. After that, I requested Kambe to make designs for our store’s wrapping papers. We didn’t give him any specific orders on designs, however, there was just one request: we would like him to express Fukuoka or Kyushu’s friendly atmosphere. We discussed it for roughly a year.

K: Usually, I don’t have a discussion on what I draw, however, through communicating with Nakagawa, his passion for his confectionary impressed me very much. I was struck by his ideas, to respect nature, to select good ingredients and materials. I can easily agree with his ideas and try to express the same with my Japanese-style painting. I enjoyed the artwork project very much.

C: What were your concerns for working on design pictures for Kakegami(a type of Japanese wrapping paper)?

K: People see Kakegami before they open the box of confectionary. I think of it as an entrance and introduction to seasonal confection. I also pay close attention to how pictures look when they are displayed on a box.

N: I thought it was a very nice collaboration between the two of them when I heard of their project because I actually had been thinking Kambe’s taste would fit the atmosphere of Suzukake’s confectionary. My mother loves collecting seasonal Kakegami, too.

C: One of your techniques of making artwork, making many layers with foil and Washi paper seems like it is based on the traditional style of Japanese art. On the other hand, the artwork itself gives us a very fresh impression. How did you come to reach this way of expression?

K: After I graduated from university, I started working at the same lab where I was studying. I had many opportunities to be involved with experts there who worked on recreating old Japanese paintings. For Japanese-style paintings in ancient times, people would paint red on the back of a silk canvas to make the color look pink from the front. We can’t do the same thing these days because we use a different type of canvas, however, I found that this technique was very interesting and thought I might as well do something similar with my art. This experience brought me the idea, using a new type of Washi for my art by making many layers. Furthermore, many types of papers are crafted all over Japan and each paper has a different impression. These combinations and expressions are infinite and I can evolve my ideas.

N: However, I think what he does is actually not easy at all, even making one layer with foil. We own one of his pieces, “The Place In the Sun”, it is 3 meters high and 12.8 meters wide, and has thousands of layers of foil. Over the layers, he decorated lotus leaves in the art design.

K: Speaking of foil, I have to be careful with using an air conditioner when I make layers with it. In summer, I need to make the room so icy cool first and turn off the air conditioner before I actually start working on the process, otherwise, foil and papers would get blown away! I need to even hold my breath as not to blow them away. In winter, there is the same kind of problem with heating. I also need to pay attention to the condition of Nikawa with temperature, it gets bad in the summer and turns into gel so easily in winter time. Materials of Japanese painting are made of things from nature, so this kind of issue makes me feel that I am dealing with nature when I work on my Japanese-style artwork.

N: Without room light, this picture shows us a different impression.

(He turned off the room light.)

Nakaoka: That’s true. It looks slightly shiny itself. Is it because of the reflection from the tatami mats?

N: I don’t know, but it always looks different depending on the weather. When we see it with candle lights, it adds a depth of feeling on the surface of the pond in the picture.

K: I think Japanese have loved our indoor-entertainment culture and it has developed Japanese -style paintings.

N: When I requested Kambe to make fusuma art, he actually said to me, “I’d like to make some tricks in my art so in 100 years, people will wonder how I made it.” As it were, he gave a riddle to people of the future.

K: I guess I’ve set my goal very high because I said something like that at the beginning. (Laugh)

Nakaoka: I think a lot of artists in the past had a similar kind of idea like his, in the field of architecture, too.

K: I think so, too. It is said that Gyoshu Hayami stated, “I created my art so that nobody would know how I did it in the future.” I also know some other painters in the past whose artworks have remained as nobody can figure out what kind of techniques they used even until now.

Nakaoka: Wow, that’s interesting! Isn’t it exciting when we imagine that people in 100 or 200 years, will still enjoy his artwork in the future?

“The Place In the Sun” (Partial)

“The Place In the Sun” (Partial)

C: How will you go about being involved with the field of Art at Dazaifu Tenmangu from now?

N: There is a photo exhibition, “Know without knowing (Kamisama wa doko?)”, by Sakiho Sakai and Kei Maeda showing there until September 7, 2014. After that, the flower art exhibition of Nicolai Bergmann runs through October 10-13, 2014, at Dazaifu Tenmangu and Kamado Jinja.

Moreover, the art program’s 9th artist is Takashi Honma and his project is now under way.

Nakaoka: I think people have started having the image, “The artistic city, Dazaifu” or “Dazaifu equals Art” these days. It used to be said that there was no place for modern art in Fukuoka, however, it’s definitely changing and getting exciting.

K: Some curators from Tokyo were surprised and asked, “Why are there a lot of artworks of top artists like Ryan Gander and Simon Fujiwara in Fukuoka?”

Nakaoka: Kambe, Nobuhiro and other great people who love art have taken over hopes of artists in the past and are now planting seeds of art culture for the future here. Having connections between many people through Art in Dazaifu is such a wonderful experience for me as one of many Fukuoka locals!

Tomoyuki Kambe

Japanese-style painter

He graduated from Tama Art University (majoring in Japanese Painting), and completed the graduate course at the same university. He was selected as a trainee under the overseas study program for upcoming artists of the Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2008 and studied Art in Boston for a year. He has participated in The Art Program of Dazaifu Tenmangu and the exhibition, “DOMANI: The Art of Tomorrow” at The National Art Center, Tokyo.

Nobuhiro Nishitakatsuji

Gonguji(deputy representative)of Dazaifu Tenmangu

After graduating from the University of Tokyo (majoring in History of Art), he obtained his master degree and Shinshoku license at Kokugikan University, and started giving his services to Dazaifu Tenmangu. He had the opportunity to be a visiting researcher of Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, Harvard University. He is also the curator of Houmotsuden(Museum) of Dazaifu Tenmangu.

http://www.dazaifutenmangu.or.jp